I wrote this kind of article before.

Feminism, PC’s Last Clean Zone: Japan

These days, not only Korea but also Western societies are all noisy with ‘identity politics.’ One advertisement, one scene in a drama, one character setting in a movie becomes a spark for controversy. On one side, there are claims like “feminists are being feminist,” “it’s tainted with PC

roughtough.tistory.com

Someone thankfully left a comment on the above article, but since my response would be somewhat complex and long for a comment, I decided to write a new article.

I remember seeing posts on Korean online communities around last year with titles like “The current situation in Japan after passing the non-consensual rape law ㄷㄷㄷ” or “Current situation in Japan after being consumed by feminists.news.” Even then, I felt that some of the content was incorrect, but explaining it would have been lengthy and slightly complicated, so I postponed it. Now that it’s come up, I want to set the record straight.

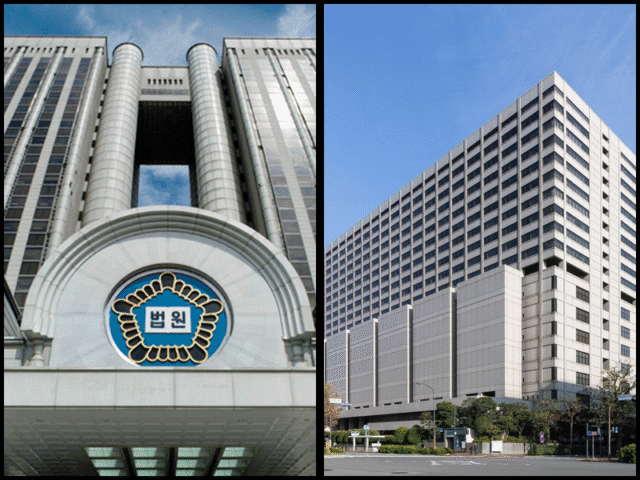

Seoul High Court and Tokyo High Court

Seoul High Court and Tokyo High Court

Korea: Crime Without Consent vs Japan: Clarifying the Scope of Rape Laws

What Japan revised in 2023 was the ‘Non-Consensual Indecent Act Law (不同意わいせつ罪)’, and its content and purpose are somewhat different from the non-consensual rape law being discussed in Korea.

The ‘non-consensual rape law’ discussed in Korea aims to delete the existing requirement of ‘assault or intimidation’ and punish as rape any sexual act without the victim’s ‘consent’. Perhaps because the requirements themselves are too broad, it has been proposed several times but faced opposition from both ruling and opposition parties, being automatically discarded in both the 20th and 21st National Assemblies, and current legislative efforts remain stalled.

Meanwhile, in June 2023, Japan revised Article 177 of its Criminal Code (rape law) to introduce a new crime called ‘non-consensual indecent act.’ However, this law doesn’t punish the mere absence of consent. It still requires one of eight specific circumstances, such as violence, intimidation, unconsciousness, or drugs, and the revision requires individual examination of whether the situation actually rendered the victim unable to resist.

In other words, in Japan, a statement of “I did not consent” alone is still not enough to prosecute for a sex crime. Prosecutors must prove in even more detail than before how that consent was taken away, that is, how the inability to resist occurred.

| 비교 항목 | 한국의 비동의강간죄 (발의안) | 일본의 부동의외설죄 (2023년 개정) |

|---|---|---|

| 처벌 기준 | 동의 부재 자체 → 처벌 | 8가지 특정 상황(위력, 협박, 약물 등) 입증 필요 |

| 폭행·협박 요건 | 완전 삭제 (동의 부재면 무조건 강간) | 여전히 위력·협박·약물 등 요소 요구 |

| 법률 통과 여부 | 발의만 여러 차례, 통과된 법안 없음 | 국회 통과·시행 중 |

| 피해자 저항 요건 | 입증 불필요 | 저항 불능 상황 입증 필요 |

| 동의 표현 방식 | 명시 규정 없이 ‘동의 안 함’ 강조 | 동의 자체는 범죄 요건 아님, 상황 판단 중심 |

| 실효성 전망 | 법안 논의 중단으로 현행 문제 그대로 | 실제 기소·처벌 사례 영향 아직 미지수 |

The legislative directions of the two countries are opposite

What’s important here is that the direction of legal reform in Korea and Japan is completely opposite.

Korea tried to eliminate the existing requirements of assault and intimidation, making ‘whether consent was given’ the central criterion. This means greatly expanding the scope of rape laws. Japan, on the other hand, still presupposes violence or intimidation, but requires an explanation for “why the victim couldn’t resist,” which is closer to making the existing criteria more explicit and specific. In other words, Japan’s revision aims to increase the effectiveness of rape laws through ‘clarification’, not to expand their scope.

How was this content transmitted to Korea in a way that led people to misunderstand? On the surface, the word ‘non-consent’ has been included in Japanese criminal law, and it appears similar in that it strengthens punishment for sexual violence. However, the actual legal structure, application requirements, burden of proof, and purpose are all different. This means that the claim spreading in Korean internet communities that “Japan has finally passed a feminist law” is based on incorrectly conveyed facts.

Moreover, in Japan’s legal community, there has been criticism that the “eight items of proof conditions” proposed in this revision have unnecessarily increased in number, potentially increasing prosecutors’ burden of proof and counteracting the intended purpose of strengthening punishment for sex crimes. In fact, some lawyers belonging to the Japan Federation of Bar Associations (JFBA) expressed at a seminar held right after the law revision that ‘while the legislative justification is good, practical enforcement may be difficult.’

Additionally, there seems to be a claim in Korean internet communities that “protests by Japanese feminist groups were instrumental in passing the non-consensual indecent act law,” but this is also far from the facts. The law revision was the result of a combination of long-standing discussions on criminal law reform in Japan, social demands for the protection of sexual violence victims, and recommendations from international human rights organizations, including the UN.

In particular, international organizations such as the UN Human Rights Committee and the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women have repeatedly recommended that the Japanese government adopt consent-based standards for judging sex crimes. Especially in their 2019 and 2022 recommendations, they pointed out that the current law fails to adequately protect against sexual acts performed without the victim’s clear consent, urging the Japanese government to revise relevant laws.

Furthermore, the Japanese Ministry of Justice held a review meeting on criminal law related to sex crimes to discuss criminal law revisions related to the protection of sex crime victims, and after nearly three years of discussions and meetings, they legislated and passed the ‘non-consensual indecent act law.’ In other words, it is correct to view it as being revised after sufficient long-term policy review and consensus process for solving institutional problems, rather than due to protests or external pressure from specific ideological groups.

In summary, Japan has never adopted the Korean model that considers the absence of consent itself as a crime.

Japan’s rape law revision still remains in a system centered on force and intimidation, just making those conditions more specific. Korea’s non-consensual rape law hasn’t even been legislated yet, but even if it is actually introduced, it would be very different from Japan’s non-consensual indecent act law according to the current legislative proposal.

I don’t know the intentions of those who misrepresent these facts by claiming “Japan has also been consumed by feminists.” However, in law, even changing a single word can alter the meaning, and without looking at the background and purpose of the law together, completely wrong interpretations can arise. It’s somewhat unfortunate that Korea’s online culture is still rampant with ‘winning the argument first’ without accurate facts.